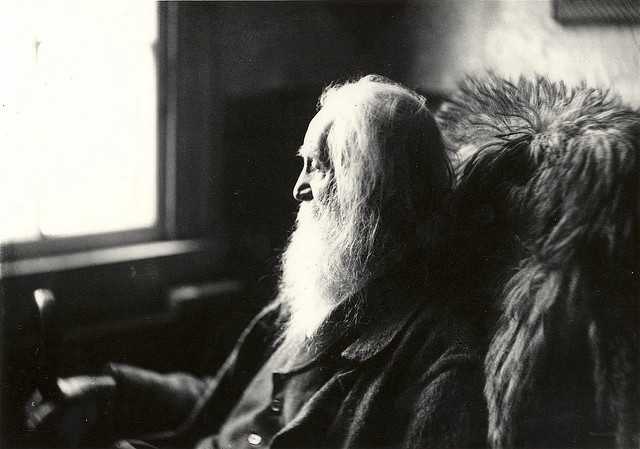

Photo by marcelo noah

Journalist and poet, Walt Whitman was called the Bard of Democracy and was considered as one of the most influential poets in the United States. He was born on May 31st, 1819, in West Hills, Long Island, New York. Walter had eight brothers and sisters and he grew up in a modest family. His own love for the United States and its democracy can be partially attributed to his parents, who admired their country by naming their youngest children after their favorite American heroes.

Walt and his family moved to Brooklyn when he was three years old, where his father hoped to make some money in New York City. However, his bad investments prevented him from achieving success. When he was 11, his father pulled him out of school so he could work, since he was unable to support his family on his own. Whitman found a job in the printing business. Conspiracy-driven politics and increased dependence on alcohol of his father, contrasted with Walt’s preference for a more optimistic course.

Whitman turned to teach when he was 17 years old. He continued to teach for another five years when he set his sights on journalism in 1841. Walt started a weekly paper called the Long Islander. However, later he went back to New York City, where he continued his career. He became editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1846. Whitman proved to be volatile editor, with a sharp pen and opinions which didn’t always align with his readers and his bosses. Walt backed what some considered radical positions on immigration, women’s property rights, and labor issues.

His job tenure was often short and in four years he was ousted from seven different newspapers. In 1848, he went to New Orleans, where he became editor of the Crescent. Whitman stayed relatively short, but it was where he saw for the first time the wickedness of the slave trade and slavery. An aspiring poet and a voracious reader, Walt returned to Brooklyn in the autumn of the same year and started a new newspaper called the Brooklyn Freeman. Over the next several years, as the slavery question continued to rise, Walt’s own anger over the issue elevated as well.

Whitman often worried about the impact of slavery on the future of the country and its democracy. During this time Whitman wrote down his observations and searched for a poetic voice that could bind together the disparate factions he was plaguing the country. After finally finding the style and voice he had been looking for, Whitman self-published a slim collection of 12 unnamed poems titled Leaves of Grass in the spring of 1855. He could only afford to print 795 copies of the book.

These poems marked a radical departure from established poetic forms. At first, the book received little attention. However, it did catch the eye of fellow poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. He wrote to Whitman and said that the collection was the most extraordinary piece of wisdom and wit from an American poet. One year later, Walt published a revised edition of Leaves of Grass which included 33 poems. Impressed by his work, Emerson dispatched writers Bronson Alcott and Henry David Thoreau to Brooklyn to meet Whitman.

During this period, Walt’s family had serious problems. His sister was mentally unstable, while his brother was an alcoholic. The second version of Leaves of Grass, just like earlier edition, failed to gain much commercial traction. In 1860, one Boston publisher issued the third edition of Leaves of Grass. This looked promising, but the Civil War drove the publishing company out of business, furthering the financial struggles of Whitman. Walt moved to Washington D.C. in 1862. His brother, who fought for the Union, was being treated for a wound he suffered in the war.

He ended up staying in the capital for the next several years. Whitman got a part-time job in the paymaster’s office and spent the rest of his time visiting soldiers, who were wounded in the war. The volunteer work proved to be both exhausting and life-changing. This work took a toll physically, but also propelled Whitman to return to poetry. Later he published Drum-Taps, a new collection that represented a more solemn realization of what the war meant for people in the thick of it.

In the years after the Civil War, he continued to visit wounded soldiers. During this period, Whitman met Peter Doyle, a train car conductor and a young Confederate soldier. Whitman had an instant and intense bond with Doyle. When his health started to unravel in the 1860s, this young soldier nurse Whitman back to health. Whitman found steady work in Washington as a clerk at the Indian Bureau of the Department of the Interior. Walt continued with literary projects. In 1870, he published two new collections – Passage to India and Democratic Vistas.

Whitman’s life took a dramatic turn for the worse in 1873. He had a stroke which left him partially paralyzed. He found it impossible to continue with his job in the capital and relocated to Camden (New Jersey), in order to live with his brother. Whitman continued to tinker with Leaves of Grass over the next two decades. In 1882, the edition of the collection earned the poet some fresh coverage in the newspaper. Thanks to good sales, he had enough to buy a modest house in Camden. The final years of his life proved to be both frustrating and fruitful.

The America he saw emerge from the Civil War disappointed him, but his work received much-needed validation in terms of recognition. His health also continued to deteriorate. Walt Whitman passed away in Camden on March 26th, 1892. Right up until the end, Whitman worked with Leaves of Grass. This collection had gone through 7 editions and expanded to about 300 poems during his lifetime. Whitman was buried in a big mausoleum, which he had built in Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery.